What elements of historical thinking have remained at the heart of history teaching over the decades?

Although different writers have given these elements different names, the process of historical thinking includes:

- Posing a question that serves as a starting point for historical enquiry.

- Gathering and weighing information about the past, distinguishing between primary and secondary sources

- Unearthing and examining as many sources as possible, evaluating them for their time of creation and potential bias

- Recognizing history involves interpretation and evaluation of information to form a narrative account

- Developing historical empathy, the ability to recognize that people living in different eras than our own had different experiences and frames-of-reference than ours.

- Understanding that historical accounts come from multiple sources that may offer contradictory perspectives, and that there often are multiple causes for an individual event. Historians acknowledge this multiplicity in developing a meaningful synthesis in their accounts.

How have history teachers responded to technological change in the 20th and 21st centuries?

Judging from the readings, at the K-12 and introductory college levels, not much has changed in the way history is taught: It still involves a “survey” that focuses on key people, events, and dates, to support “good citizenship” and inculcate social values into students. The technology of the print textbook is little changed, although today “interactive” ebooks have been introduced that offer the opportunity to link to source documents, videos, simulations, and other materials. However, my experience as a textbook editor is that the interactive features found in these books have not been widely assigned by teachers and therefore not widely used by students.

In the public history sphere, there has been an embrace of digital history, beginning with a large effort by major institutions (such as the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian) along with universities to digitize their archival collections of historical maps, images, and source documents. Google Books has digitized thousands of books, and sites like the LOC’s American Memory and commercial providers like newspapers.com have made large archives of historical print accounts available for easy searching. This has given historians the ability to more quickly amass source materials that in the past. Various interpretative sites have drawn on these materials, although most are only funded and kept current for a year or so after they are initiated, so there is a wide variety of sophistication and currency of material currently online. Many teachers have drawn on this material to enhance their teaching and student learning, either through having students do basic archival research or to work with interactives developed by historical societies, museums, and other sources.

How have external expectations constrained teaching and learning in history and how might the digital turn disrupt those constraints?

All the authors note that the general public’s perception of history is that it’s just, in Henry Ford’s words, “just one damn thing after another.” Rote memorization of names and dates is viewed as the major objective for history students and the advent of curriculum standards and standardized testing has only exacerbated this viewpoint. Viewing history as an amalgam of “facts” has led to an ongoing public discussion of “who’s history” is valid. Conservatives push for teaching the “great men” and “key events” that they see as central to American history, and balk at those who even suggest adding a few alternative voices or narratives to augment or enhance the story. Liberal thinkers suggest that individual histories are all equally valuable, so that teaching any one set of facts over another is necessarily biased and dangerous. This entire argument, of course, is predicated on the thinking that history is necessarily an exercise in defining national identity through a clear, compelling, and patriotic narrative of facts and events.

Digital resources could help history teachers break their dependence on the standard text. Instead, they could draw on a much wider palette of source materials and interpretative sites to tell a richer story beyond the confines of a march of names and dates. Rather than focusing on the ingestion of an approved set of facts, historians could engage students through encouraging them to practice the historical method. This would include working with digitized primary sources, participating in virtual enactments, using mapping and analysis tools, and other approaches that are facilitated through engagement with the digital world.

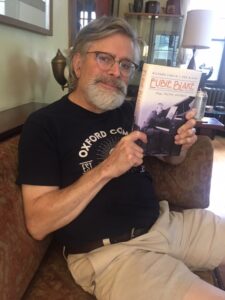

I’m Richard Carlin, and I’ve been an editor and writer of books on the arts for over 30 years. My latest book is Eubie Blake: Rags, Rhythm, and Race (coauthored with Ken Bloom; Oxford U Press, 2020), and I have published several books on country music and popular music history.

I’m Richard Carlin, and I’ve been an editor and writer of books on the arts for over 30 years. My latest book is Eubie Blake: Rags, Rhythm, and Race (coauthored with Ken Bloom; Oxford U Press, 2020), and I have published several books on country music and popular music history.